North Macedonia and COVID-19: The Long-Necked Monster

*This blog is published as part of the regional blogging initiative “Tales from the Region” on the experience of western Balkan countries with the COVID-19 Pandemic, published between 24 June 2020 and 6 July 2020. The initiative is coordinated by Res Publica (North Macedonia), in partnership with the Institute for Democracy and Mediation (Albania), Analiziraj.ba (BiH), KIM Radio (Kosovo), Sbunker (Kosovo) the civic initiative „Ne Davimo Beograd“ (Serbia) and PCNEN (Montenegro).

Author: Anastas Vangeli

The trend of putting up walls between states and the shaky confidence in the multilateral order suggests that the pandemic, instead of being resolved as a global crisis, will continue to be resolved as a national crisis in each country of the world. Taking all this into account, COVID-19 is also the biggest test of how much and how successfully North Macedonia can act as an independent state in the world that is ever so rapidly changing.

Although many global risk reports indicate infectious diseases as one of the biggest threats to world politics and the economy, in early 2020 few countries in the world were prepared for a global pandemic of a new, hitherto unknown respiratory pathogen such as the novel coronavirus. Even the initial reactions to COVID-19 across many parts of the world seemed to underestimate the situation.

North Macedonia during a pandemic

When the first major hotbed appeared in Wuhan, North Macedonia did not take significant preventive measures against the impending danger. Italy, on the other hand, was closer to home; and the first people coming back from abroad and were positive for COVID-19 sounded the alarm. When cases of local transmissions were confirmed, the state began more comprehensive testing and the introduction of more rigorous safeguards throughout the country, the implementation and observance of which varied across different places and different social groups.

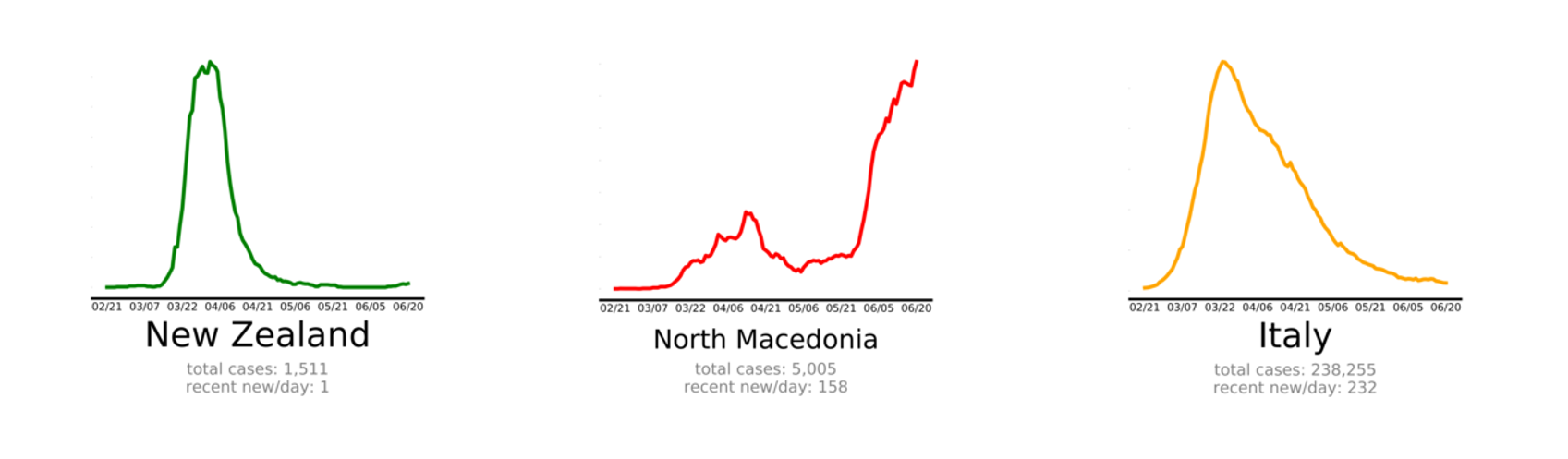

Once the spread of the infection was brought under control in early May, the number of cases began to rise again in June. At the time of writing this text, at Worldometers, North Macedonia ranks 53rd in the world in the number of cases per 1 million inhabitants and 34th in the world in the number of deaths per 1 million inhabitants.

The curve of daily new cases in the country, which seemed to be declining, is going haywire in recent days – as a result, it resembles the “Loch Ness monster” – with a hump that goes down, and a large neck that rises to the sky. The difference is that the Loch Ness monster is a mythological creature, created through folklore in the Scottish Highlands. Our chart monster is real, aggressive and deadly.

However, it is currently unclear whether there is capacity for strong and uncompromising handling of the infection in North Macedonia. In North Macedonia, the adage of leading American epidemiologist Dr. Fauci that “the virus makes the timeline” (not the institutions) does not hold true. The lifting of the state of emergency coincided with the flare-up of the number of new cases. The Crisis Headquarters and the Commission on Infectious Diseases have started to take differing stands. After three months of wading around in shallow water, the fourth month is when the system plunged head-first into the impending tsunami.

However, the state and its (un)preparedness are just a part of the story of dealing with the pandemic. The other part is society’s reaction – the behaviour of citizens at all levels – primarily, their personal awareness and measures of self-protection, behaviour in the family, in everyday socio-economic interactions and in the workplace. Wearing respiratory masks, maintaining physical distance, self-isolation when showing the slightest symptoms, and reducing or stopping production or other economic activities, even after a few months of the global pandemic, are not generally accepted practices. Of course, this is not the case only in North Macedonia – but the fact that such problems exist elsewhere cannot be a consolation to anyone.

The reasons for slow learning are varied: lack of education, lack of willpower and conviction (some of our fellow citizens do not believe that COVID-19 exists), exposing oneself to (mis)calculated risk, or lack of conditions and choice (for example, workers who are forced to go to work despite evident risks, so as not to lose their jobs). The way the virus is transmitted means that those who do not keep distance, regardless whether they are members of the elite or if they are ordinary citizens, even if they are few in numbers (which they are not), have a disproportionately strong effect on exacerbating the spread of infection.

Structural problems

Meanwhile, the world continues to sail in an unknown direction, which in turn is a source of new kind of insecurity and fear, even in societies like North Macedonia that are accustomed to living in uncertainty and all kinds of shocks.

From an idealistic perspective, enemies who stand to threaten all of humanity should awaken greater empathy, solidarity, and cooperation. However, reality shows otherwise. COVID-19, instead of acting as a unifier, has so far acted as a catalyst for existing political and economic opposing views, at all levels – from growing tensions between world superpowers to distrusting family and neighbours.

Dealing with the multi-layered crisis brought upon by the virus also reveals structural weaknesses of societies and institutions – including the conflict between the desire to be safe and the desire to be free felt by humans around the world; between the sanctity of human life and the inviolability of socio-economic activity; and between the incredible scientific and technological advances on one hand, and the anti-scientific positions of the people, both coming from the elite and the masses all over the world, on the other.

In North Macedonia, the virus has shone a clear light on the contrast between the need for a holistic view of things and the reality of fragmentation of the system; the conflict between the system based on public relations against the underdeveloped principle of regard for the people, the conflict between “pleasing” different social groups and the need to care for society as a whole, and the conflict between the hope that help can come from outside and the isolationist tendencies produced by the pandemic.

Firstly, dealing with COVID-19 is impossible without absolute prioritization of the fight against the virus, a holistic view of things, effective cross-sectoral communication and the coordination and mobilization of all available resources, in order to suppress the infection. Unfortunately, there is still no model in the world that can fully meet this challenge, although some countries have proven to be better at it than others. However, all public administrations in the world suffer from the problem of fragmentation and irrationality of bureaucracy.

But what is very specific to North Macedonia is the fact that managers are assigned not by merit, but through partisanship and ethnic quotas, which in turn contributes to a reality in which different institutions or officials are pulling in different directions and are drawn and instrumentalised in pursuing separate interests, even in times of crisis.

The North Macedonian context in which COVID-19 takes place is a particularly fertile ground for chronic problems to escalate. The outbreak of COVID-19 happened at a time when North Macedonia is under a caretaker government, with a limited term, in which political enemies co-exist in order to organize the fifth early parliamentary elections in the last 14 years. As the election date approaches, internal tensions in the system are expected to intensify – not only between political parties but also between commissions, between managers and people working on the field and between institutions and their employees.

Secondly, the political fight for public opinion in the digital age is fought 24/7, in every corner of our existence. The media space, which is contaminated with sensationalism, further contributes to the intensification of that fight. Putting aside the collateral damage caused in the domain of public discourse as a direct result of this political-media constellation in the time of COVID-19 (misinformation, fake news or propaganda), the basic problem is that a disproportionately large part of the legitimacy of institutions is based on the outcome of these fights in the field of public relations, and much less than the material, the everyday regard (of the institutions) to the people.

Specifically, this means that (even) during a pandemic, the fight arena for public opinion is receiving much more attention, resources and energy than it deserves, at the expense of the frontline in laboratories and hospitals, or the frontline in the economy. For decision-makers, public opinion is a priority. Subjective interpretations and beliefs are the criteria by which the (lack of) success in all other fields is gauged. In other words, as long as the great debate over COVID-19 revolves around the numbers of treated, infected, healed and deceased, those numbers (will) only partially affect the creation of policies; the numbers that essentially shape policies and political positions are clicks, likes, and poll percentages.

Thirdly, and on a related note, a problem of a COVID-19 scale requires fast manoeuvring and making uncompromising, often unpopular decisions, especially in regulating some of the basic human rights (the right to free movement). In fact, protests have been held in many parts of the world against measures to restrict movement. In North Macedonia, initially, the relatively early and decisive regulation of the movement was a factor that contributed to the initial success in the fight against COVID-19.

But the balance-weight was too strong to maintain that type of rigorous and slightly arbitrary (from today’s point of view) effective measures. Long and comprehensive curfews triggered resentment among some people with liberal views, people with hazardous tendencies, or simply people who did not want to stay home; closing down catering and other businesses was a major blow to the entrepreneurial class, but also to their employees; while in one of the world’s most religious societies it was impossible to dissuade religious communities and believers from engaging in risky behaviour during the holidays.

These parts of the population – and especially among believers – were the place where a new, wider wave of infection has begun. But in addition to the risky behaviour that has led to the spread of the virus, a new general feeling of division, finger-pointing and spiralling hatred on various grounds (including ethnic-religious identification) has emerged as a response. All this adds another layer of risks associated with COVID-19, related to the potential reignition of ethnic (political) tensions, which can further paralyze the system, and thus make it difficult to get out of the crisis situation in the short term, and in the medium and long-term jeopardize the functioning of society even in the post-pandemic period.

Fourthly, COVID-19 is paradoxically the biggest global crisis of our time, and at the same time, it is the first major crisis that North Macedonia will have to deal with on its own, without too high expectations from the international community. The current crises in the country have been resolved with strong participation of external actors; which was accepted as part of the strategy of the main political actors. In the context of COVID-19, external actors will be present, some of them will influence the development of events in the country in various ways, but because they themselves are facing the challenges of overcoming and recovering from the crisis, they will have far less of a share during the events compared to previous experiences where their role was decisive.

In general, the trend of erecting walls between states and the shaky confidence in the multilateral order suggests that the pandemic, instead of being resolved as a global crisis, will continue to be resolved as a national crisis in each country of the world. Taking all this into account, COVID-19 is also the biggest test of how much and how successfully North Macedonia can act as an independent state in the world that is ever so rapidly changing.

The duty to look ahead

The above reflection of the situation does not allow us to take too much of an optimistic outlook on what comes next. This text locates the birth of the “long-necked monster”, which is likely to haunt us for at least a few more months, primarily in structural factors that largely determine the outcome we see today: it probably could not have gone otherwise. But that predestination for a rather unfavourable social outcome does not mean that we are helpless at the level of individuals and that we need to surrender to the situation – to the contrary. We are in for a long and hard battle on two fronts.

First, today it may be even more important to stress that we must survive. When the “big picture” is scary, individual responsibility is what everyone owes to themselves and their loved ones. But even more important is the second front – and that is the front of pro-active thinking, action and (pre) mobilization. The monster, no matter how much it is a source of fear and suffering, is at the same time a large mirror, which clearly shows all the weaknesses and shortcomings of the world that produced this crisis, and which, unlike most of us, will not survive. As the old world slowly fades out of our memories, space opens up for us to create a new, better one – although there are no guarantees as to what kind of new world we will be living in a few months or years from now. The virus has shown us that our limited knowledge and imagination no longer allow us to predict what will happen in the short or medium term.

However, this openness of the future, combined with the fact that the stakes are now high for each of us, suggests that the COVID-19 crisis also has emancipatory potential. The state has a duty, in parallel with the fight against the virus, to recognize and harness that potential. In particular, understanding the complexities we have yet to face must be part of both the work of the state and public discourse. In addition to the Crisis Headquarters, North Macedonia needs an independent advisory body that will make an effort to understand the unknown future, which will aim to establish basic notional parameters for how the state – ruined by COVID-19, but also by depreciated stress of all previous crises, and with a wobbly structure – will need to be built and adapted. That body will have to act even against the political mainstream, and restore faith in knowledge, science, and the unbreakable nature of the human spirit. The extent to which the work of such a body will affect policies remains to be seen. Until then, good health to us all.

About the author: Anastas Vangeli is a doctor of social sciences. He is a lecturer at the Shanghai Campus at the ESSCA School of Management, France and a researcher at the ESSCA Institute for EU and Asian Studies. He is also an external senior contributor to the China and Mediterranean Project at the World Policy Institute in Turin (T.wai), Italy.