COVID-19 and Kosovo: a triple crisis

*This blog is published as part of the regional blogging initiative “Tales from the Region” on the experience of western Balkan countries with the COVID-19 Pandemic, published between 24 June 2020 and 6 July 2020. The initiative is coordinated by Res Publica (North Macedonia), in partnership with the Institute for Democracy and Mediation (Albania), Analiziraj.ba (BiH), KIM Radio (Kosovo), Sbunker (Kosovo) the civic initiative „Ne Davimo Beograd“ (Serbia) and PCNEN (Montenegro).

Author: Edison Jakurti

If we are to use a single adjective to describe the economic crisis caused by COVID-19, then it is: unprecedented. This is because its scale is global, and the reason is also valid across the world. However, we should keep in mind that it is happening in times of great crises: in capitalism, crises are inherent and almost periodic. Therefore, COVID-19 is more of a spark than a cause of the economic problems we face.

The current economic crisis, although unprecedented, is separated from the past. To put it in other words: there hasn’t been a crisis of this type in the past, but we have constantly witnessed different crises. While this one is unusual, there is space for comparison. For example, some have compared this crisis to a war crisis.

Knowing that Kosovo’s economy has not contracted since the war, and because we are currently expecting a contraction, war is becoming a reference point in history. And since there aren’t many studies on the region’s economic history, it’s probably worth recalling the challenges of the not-so-distant past.

The largest economic depressions in the Western Balkans

While developed countries have as a reference point the Great Depression of 1929-39, or the Great Recession 2007-2009, the six Western Balkan countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Republic of Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania and Serbia), which are not part of the European Union, have experienced their greatest economic crises during the wars and economic and political transitions in the 1990s.

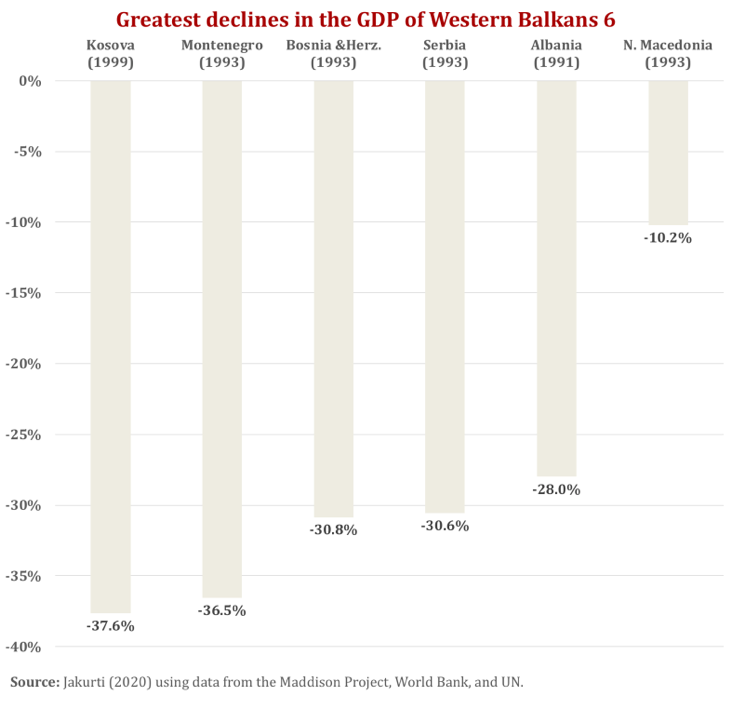

As a reminder, the technical definition of depression in the economy is the situation when the annual decline in the gross domestic product (GDP) exceeds 10%. And, in general, thanks to the historical data from the ambitious database of The Maddison Project, the largest depressions in the history of different countries around the world can be calculated. As we can see in Figure 1, all six Western Balkan countries (WB-6) have had such declines in the past.

Of these historic declines, the mildest decline was in North Macedonia in 1993, when the annual economic growth was around -10.2%. While the biggest decline was recorded during the Kosovo war, in 1999, when GDP registered an annual decline of around 37.6%.

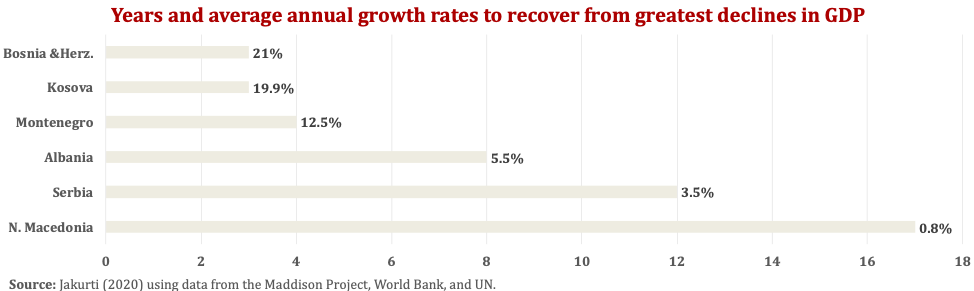

The recovery (return to the initial state – before depression) was different both in terms of duration and in terms of annual growth rates. For example, as seen in Figure 2 below, the Republic of Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina recovered faster. This is due to the fact that the economic base was smaller and the average economic growth for those years was higher.

Yet, despite much uncertainty, not even the biggest pessimist today expects the current crisis to be characterized by such a drastic drop in GDP as it was in the 1990s. The International Monetary Fund describes the current crisis as a crisis like no other. The World Bank also sees it as the deepest global recession in recent decades. Nevertheless, even their most pessimistic forecasts are nowhere near the ones shown in Figure 1.

Similarly, not even the biggest optimist can expect similar annual growth rates, since a lot has changed since then – from the rise of domestic economies to the dynamics of their integration into global markets. And the time it takes to recover from the current crisis will largely depend on governmental policies. This can be further complicated when there is a political crisis, as is the case with Kosovo.

The triple crisis in Kosovo and the (lost) opportunity for economic change

While most countries in the world have faced a two-fold crisis in terms of their health and economy, Kosovo has been going through a threefold crisis, due to political developments. This culminated with the first case in the world of an overthrown government during the pandemic, with the government of Kurti being overthrown through a “peaceful coup”, 50 days after its formation, and replaced with the government of Hoti. A strong reason, among other things, for this coup, was that Kurti’s government was seen as an obstacle to the plan to divide Kosovo, something that could have been a key part of the agreement that would come out of the dialogue with Serbia.

While measures taken to manage the health crisis in the world have reduced the economic crisis, the political crisis in Kosovo has further exacerbated the health and economic crisis.

Despite the fact that they inherited a health system with numerous problems, Kurti’s government managed to make Kosovo one of the most successful countries in the efforts to flatten the curve of infected cases. We remind you that about 1 week before the vote of the Government of Hoti, exactly on May 24, Kosovo had 0 new cases and, by that date, there were 29 deaths.

Hoti’s government was elected on June 3, with a minimum number of votes needed, only after the state president paid an after-midnight visit to the home of the “deciding” MP to form the government. And, as seen in Figure 3, this is the time when the enormous growth of newly infected persons began.

Of course, this coincides with the gradual opening of the economy, which was previously planned by Kurti’s government. But now the government of Hoti has taken over the management of the country and the management of the pandemic, which he described as one of the two main priorities, along with economic recovery.

The results of this prioritization are best illustrated in Figure 3. What we have seen so far from the Hoti government is not management, but surveillance of a pandemic and a threat to citizens through “insubstantial” press conferences.

Just over a month after Kosovo recorded 0 new cases, for the first time in Kosovo, on June 29, we had over 100 new cases (122 cases to be exact) and a total of 49 people who lost their lives. We recorded similar numbers in the following days. All this after the recommendation not to test asymptomatic cases of contact, which means that the number of infected people may be even higher and that many cases infected with the virus may remain unidentified. There is currently a lack of transparency and the country’s health facilities appear to be reaching full capacity.

Despite the large difference between health crisis management, we have a fundamental difference in the approach to the economic crisis. Kurti’s government was in the process of completing the implementation of the Emergency Fiscal Package when it also announced the Economic Recovery Package. This was an ambitious plan of about 1.26 billion euros. In particular, this package provided:

- Loan for enterprises and households;

- Grants for young people for innovation and practical work;

- Employment and formalization plan through salary subsidies;

- Salary subsidy plan in the hospitality industry (HORECA);

- Scholarships for pupils and students and grants for educational institutions and enterprises;

- Anti-Poverty Plan;

- Grants to support community projects implemented by non-governmental organizations;

- Authorization to exceed the fiscal threshold in 3 years;

- For expatriates: Coverage of green card costs, more favourable terms for securities, and financial support at the airport “Adem Jashari” in order to offer more favourable ticket prices for travellers coming to Kosovo;

- Filling the state reserves with the basic products produced in the country;

- Start of work for the establishment of a Sovereign Fund for Public Enterprises.

In fact, this did not only seem like a recovery plan but also a turning point for potential economic development. Through it, new paths could be created that would enable the solution of the biggest economic problems that Kosovo has, and some of them could become worse as a result of the crisis.

For example, the chronic problem of the Kosovo economy is structural unemployment – mainly as a result of the gap between educational preparation and the skills required in the labour market. But as a result of the crisis, cyclical unemployment will also become a problem – largely due to the inability of companies to retain workers.

Or, the problem was the high interest rates that made it difficult to access capital for micro and small enterprises. Now, when the lack of economic activity has reduced profits, in addition to increasing the need for liquidity, the risk of the inability to repay loans has increased – and access to capital could continue to deteriorate.

On the other hand, there were indications that some of the biggest problems of the Kosovo economy, such as the high trade deficit, were improving. May was the third month in a row that Kosovo registered a drop in the trade deficit (in goods) compared to last year. According to data from the Kosovo Statistics Agency, exports were about 38.7m euros this month and imports about 239m euros, in which case the trade deficit was about 200.3m euros. Compared to May of last year, this was an increase of about 21.6% of exports, a decrease of about 25.7% of imports and a decrease of about 30.9% of the trade deficit. This decline in the trade deficit of goods is just another indication that the pandemic is an excellent opportunity for intervention in the structure of the economy.

But what happened with the arrival of Hoti’s government is a remarkable example of how the old government does not avoid any crisis, instead, they use crises as a refreshment of the status quo.

Although their economic recovery plan has many elements taken from the plan presented by Kurti’s government, none of them are being implemented. The exception to the “borrowed” measures is the dangerous idea of creating an opportunity to withdraw 10% of the pension fund, which would create more problems in the future. In addition, as part of the economic development plan, what the Hoti government promises is the privatization and asphalting of roads, which means a continuation of neoliberal tradition, meaning going back to “business as usual”.

It should be noted that crises can be unusual challenges, but also great opportunities. They create moments where ideas that were once politically unacceptable become economically inevitable. It seems that the current government will not last long, but it is certain that it “stole” the extraordinary chance caused by the pandemic to start with the big changes in the economy.

Still, the necessity for these changes means that we do not have to wait for another crisis in order to put them in motion. Simply, what is needed are new elections and a new government. Initially, to stabilize the state of health and to obtain an economic recovery. This would be followed by a development that transcends economic growth.

About the author: Edison Jakurti is a PhD Candidate in Economics at the Freie Universität Berlin. Recently, he was appointed Deputy Minister of Economy, Employment, Trade, Industry, Entrepreneurship and Strategic Investments in Kosovo. He earned his Master of International Development Policy degree, concentrating in Applied Economics, from Duke University, and his BSc degree, majoring in Economics & Statistics, from R.I.T. He has worked as a research and teaching assistant at Duke University, and as a consultant at the World Bank in Washington, DC.