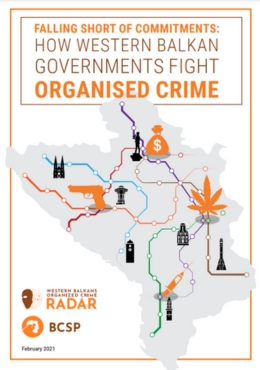

Falling short of commitments: how Western Balkan governments fight organized crime

Fight against organised crime has been, at least at least according to officials’ statements, on top of the agendas of Western Balkan governments for almost a decade now. This commitment was often just a declaratory one, brought on by external actors, such as the EU through the accession process which encompasses the WB six and puts emphasis on the need to more effectively tackle the issue of organised crime. While the enlargement perspective was still considered credible and alive, the governments had an incentive to invest efforts in dismantling organised criminal networks that traditionally have been organised better than the governments themselves. With the onset of the so-called enlargement fatigue and no certain European future for the WB six, these incentives disappeared. As a result, and coupled with the absence of a genuine, organic drive to deal with organise crime within the WB countries, citizens’ hopes of living in crime-free societies started disappearing as well.

This research report investigates a part of the above described problem. Namely, it attempts to determine why the governments are falling short of their commitments relating to organised crime. The question that needs to be addressed first is how anyone can even assess the effectiveness of the fight against organised crime in the WB6. While it is a general understanding that the results leave much to be desired, there is a also gap in both administrative and survey-based statistical data available to the public that makes it difficult to establish how effective state responses against organised crime truly are. This leaves room for competing narratives about the achieved results, and this is why it is possible for one WB government to claim that it is leading a highly successful war on mafia while, at the same time, there are credible reports and leading experts claiming that the same government is deeply criminalised and that its war on mafia is nothing but a media stunt.

The very first challenge identified in this report is the lack of credible data on organised crime, which happens to be the single biggest obstacle to an evidence-informed public debate on the issue. Although this has already been recognised, it is worth reiterating that most countries in the region do not have statistical systems in place that are able to collect and monitor data on organised crime. Even when these systems exist, data greatly varies from one type of crime to another, or it is not segregated to allow for a meaningful analysis. Tracking a case through the criminal justice system is especially difficult, because there are no unique identifiers that would allow it. Moreover, data from institutions are usually not readily available, and, even after obtaining it through freedom of information requests, few conclusions can be drawn because of case management systems that use different indicators that prevent meaningful comparison.

The second key finding is that, although legal and strategic preconditions are largely in place across the Western Balkan Six, it is the implementation that leaves much to be desired. Law enforcement agencies often lack sufficient capacities, proper coordination and resources to be able to successfully fulfil their mandates. Furthermore, it is a general opinion of all the interviewed interlocutors that good cooperation of law enforcement agencies is the most important factor in the fight against organised crime. Although bilateral agreements are in place, and there is a host of regional and international fora that enable such cooperation, there are also obstacles that prevent more effective cooperation and a better coordinated response.

Finally, politics play a significant part. Whether in the form of political influence on law enforcement agencies, lack of political will to combat organised crime, or a political decision not to fight it at all, it appears that politics is the main obstacle to having better state responses to organised crime in the Western Balkans. It was stated in the EU’s Credible Enlargement Strategy of 2018 that “the countries show clear elements of state capture, including links with organised crime and corruption at all levels of government and administration.” Political leaders are therefore, and simultaneously, the key problem solvers and the main problem that needs to be solved, which is why it is up to them to ultimately assume responsibility for creating an environment conducive to fighting organised crime and boosting societal resilience to the harm it causes.

Click to download the research report in English Albanian

Opinions expressed in the publication are sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Netherlands Embassy in Belgrade, Royal Norwegian Embassy in Belgrade, the Balkan Trust for Democracy, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, or its partners.